One approach to understanding uncertainty in its most general sense is to consider some simple examples of uncertainty and use them to derive a general approach to managing uncertainty that can guide us in our daily lives. Let’s consider what the weather may have in store for us on a particular day – will it rain or will it brighten up? In the United Kingdom this is a particularly tricky uncertainty, and one that we need to deal with, if we are not to risk a soaking or to overheat in winter clothes should the sun emerge after a cool and cloudy start. And so if we are prudent we will check the weather forecast before we go out, and will take a decision on what preventative action to take, for example, carrying an umbrella or a sun hat, to minimize the consequences of the uncertainty. We will then get on with our day, all the time keeping a watchful eye on the weather to see if our plans for the day will need to change. This is a trivial example of uncertainty, where generally speaking the repercussions of error are not disastrous. The second example we will use here may have more serious consequences, and is concerned with the uncertainty in how long we may live. We may die young or we may live to a ripe old age and whilst there may be information that we can gather to help assess the likelihood of each of these scenarios, for example family medical history or current lifestyle choices, we will never be absolutely certain of our lifespan upon this earth. All that we can do is to take preventative action in the light of the information gathered, for example by eating more healthily, taking regular exercise and having appropriate medical check-ups. Again the best we can do is stack the cards in our favour and move forward.

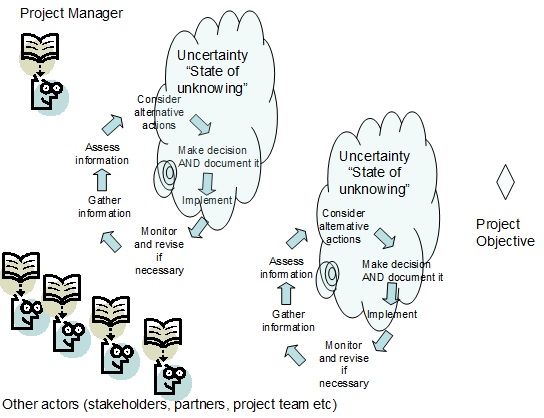

From these two examples it is possible to posit a simple model for how we intuitively deal with the day to day uncertainties with which we are confronted. This is illustrated below.

When faced with a “state of unknown” or an uncertainty our first response is often to gather information pertinent to the uncertainty in an attempt to reduce it. We check the weather forecast for example. We are pragmatic in our information gathering phase, knowing instinctively that gathering information has a cost, for example it may delay us getting out to enjoy the day, so we gather quick, but relevant information, allowing us to proceed to the next step in managing the uncertainty – that of considering our options. In our weather example this would relate to what clothing to wear and what to take with us, or if the weather forecast is extreme we might consider changing our plans completely. Having considered our options, we are then required to make a decision on a course of action and move forward. In the second example this might involve starting a programme of exercise. Having done this we will then regularly review our decision in the light of emerging information, for example the results of a future medical check. Of course there is always an alternative course of action open to us in the face of uncertainty, and that is to press on regardless, ignoring the uncertainty and dealing with any consequences as they arise.

When faced with a “state of unknown” or an uncertainty our first response is often to gather information pertinent to the uncertainty in an attempt to reduce it. We check the weather forecast for example. We are pragmatic in our information gathering phase, knowing instinctively that gathering information has a cost, for example it may delay us getting out to enjoy the day, so we gather quick, but relevant information, allowing us to proceed to the next step in managing the uncertainty – that of considering our options. In our weather example this would relate to what clothing to wear and what to take with us, or if the weather forecast is extreme we might consider changing our plans completely. Having considered our options, we are then required to make a decision on a course of action and move forward. In the second example this might involve starting a programme of exercise. Having done this we will then regularly review our decision in the light of emerging information, for example the results of a future medical check. Of course there is always an alternative course of action open to us in the face of uncertainty, and that is to press on regardless, ignoring the uncertainty and dealing with any consequences as they arise.

The two examples above and the associated simple model for managing uncertainty may seem trivial but they do serve as a useful thought experiment/precursor to us understanding how project managers manage uncertainty in projects. In a similar spirit to the above examples from everyday life let’s now consider an example very familiar to any project manager – the length of time a particular project task will take, whether 1 week or 2 weeks and the level of uncertainty associated with each of these time estimates. In this scenario the prudent project manager would gather information – how long have similar tasks on past projects taken, how long do those responsible for the task think it will take, what are the influences on task time and can they be minimised etc. This information would have to be assessed by the project manager who would then be in a position to consider a series of alternative actions such as employing additional resource to bring the task time down, reworking the project plan to take into account the uncertainty in task duration, or advising stakeholders that the expected task duration is 2 weeks. Of course this list of actions is illustrative rather than exhaustive and the exact range of actions would depend on the context of the project. The project manager would however be required to make a decision on which course of action to follow and if prudent would regularly review that decision in the light of any emerging new information. An important additional step in the management of project uncertainty is also to document the decision made, and the assumptions on which it is based in order that the rationale for the action can be understood and recalled at a later date – otherwise the project can appear to be built on shifting sands, with no clear markers in the ground. As in the non-project examples above, the project manager can also choose to ignore the uncertainty in task duration and deal with any resultant impact on the project completion date as and when it arises.

The use of a real project example helps us to validate and extend our original simple model of managing uncertainty as follows.

The most significant amendment we need to make is the size and location of the project objective. In the example of the weather and the length of our life the project objective may be ill defined, for example to live as long as possible or to enjoy the day, whereas in the case of the world of project management the project objective is generally but not always more well- defined and comprises a set of objectives (at the early stages of the project there is likely to be less clarity around these objectives). In addition the project will most likely contain a number of uncertainties, about resource requirements, organisational priorities, or regulatory requirements each of which may be independent from or interdependent on the others, and which must be managed in through the same iterative loop of action. Lastly our project management specific model highlights that the project manager is no longer a lone individual but is only one of a number of project actors, whether stakeholders, project sponsors, or members of the project team each of whom will have different information, knowledge, perspectives and agendas to bring to bear on the project.

The use of these simple examples from both the everyday world and the specific context of project management helps us begin to construct a model for managing uncertainty from first principles, or from reflection on what we intuitively do in our daily personal and professional lives. The next step in our explorations (and the subject of my next blog post) is to unpack the various definitions of uncertainty that are presented in the project management literature and attempt to disentangle uncertainty from the more familiar project management concept of risk.